First part : Celine and Julia Go Boating : Subversive Fantasy

1. To emphasize the fantasy aspect of the city, the framing utilizes the lines of streets and pathways (left), staircases, balustrades, and walls to vary the composition drastically from one shot to the next. Julie covers her face with a scarf Celine had drooped when "caught ." Celine stands next to her own poster as a magician. Julie waits outside a pension that Celine had checked into, while Celine peers down at her pursuer below. The next morning Julie returns, finding Celine in the cafe below. Acknowledging the sexual politics of the sutation, Celine laughingly receives her scarf back with a "Thanks, sir."

Communicating on their turf

2. Men control and shape the social parameters of nightclubs, nightclub districts, porn establishments, and bars. This social structure formalizes access to women ; voyeurism here also serves as a metaphor for film viewing. The bosses wear the male uniform of power, suit and tie ; the ones in control, they indicate by their body language that they consider their authority a given. The less powerful and more socially insecure (e.g., women, children, servants) show more attentiveness or immediacy in their body language. As Celine’s stand-in, Julie will later deliberately subvert the bosses’ "potency. »

3. Film costumes reflect power and status relations ; here there is a paradigmatic opposition of man in suit vs. woman half-dressed. The manager unilaterally violates Celine’s personal space ; he pushes her up against a door, addresses her like a child, and tries to negotiate a contract while she has cream on her face.

Working women understand the humiliation and manipulation inherent in their boss’ asking personal questions, using their first names, touching them, and considering them "emotional." Hen generally find it hard to imagine that women often do not want to talk to or pay attention to them.

4. At Madlyn’s birthday party, the deep-focus cinematography keeps all the lines of action contained within the frame and emphasizes through repetition of verticals the characters’ rigidity. The milieu is affluent, sterile, and claustrophobic.

The characters are atomistically separated and locked into a pattern oriented around Olivier, who owns this space both materially and emotionally. Contrast this to an ordinary party, where people signal interest by proximity, forward lean, directly facing shoulderangle, legs and arms moderately open if seated, and frequent smiles and nods to maintain conversation.

5. In a Jane Eyre-type oedipal fantasy, the nurse hopes that the older man, higher in social status, will offer her security and romantic love. Here Angele and Oliver act self-conscious about their bodies and pysical closeness, indicating sexual attentiveness. Olivier’s unilateral direct gaze at and shoulder orientation toward the woman indicate male dominance. Angele-

Celine smiles often, cocks her head, and glances up while speaking — culturally accepted gestures of female responsiveness. Oliver’s pass ironically reinforces our sense that patriarchal authority "orders" this milieu.

6. Sophie is the evil governness and the femme fatale. She is cold, immaculately groomed, and glamorous by middle class standards ; and like the wicked witch in patriarchal fairy tales, she injects the child’s candy with sedatives.

Glamorous dresses are usually tight and restrictive ; the glamorous woman’s power resides not in physical movement but in being manipulative, deceitful, and sexy — like Cleopatra or Medea. As in many of the shots in the crime melodrama, the composition shows Sophie "caught" in the architecture of this rich family mansion, which one of the women will get along with Olivier when and if the little girl is out of the way.

7. The characters in the interior story follow rigidly defined paths of prescribed movement. They do not make unpredictable gestures, only very "dramatic" ones that underscore what we might predict, especially about emotional life in the domestic sphere (similar to soap opera and melodrama). The composition characteristically isolates the human figures.

Camile wears red, has bouffant blonde curls, and represents another female type : emotional, pouting, dependent, and always whining.

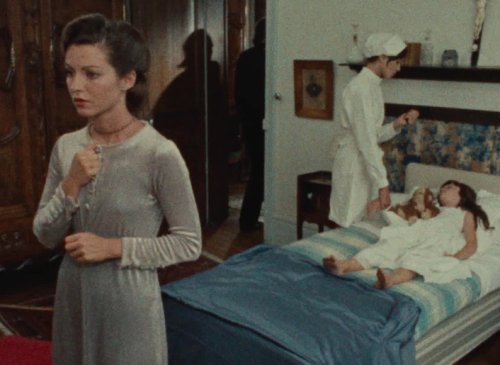

8. In the interior story, the child is vulnerable and manipulated. She is always depicted in "correct" poses and is never messy. Her pulse is weak and she’s sick and sleepy. In the family it is the woman who enacts patriarchy’s mandate to repress (here, murder) the female child.

"Could it be Angele ?" asks Celine and Julie the morning after they tripped together, now lying on the couch with the sun pouring in. By keeping the little girl alive, they also extricate themselves from Angele’s complicity with the evil "stepmothers." That is, they learn to offer each other authentic womanly nurturance.

9. Camille has cut herself on a glass and is being treated by Angele (the source of the bloody hand on Celine and Julie’s backs).

Her blown hair, vacant look, and sagging posture make her seem helpless and dependent. She has dressed up in her dead sister’s dress to win Olivier and so to get possession of what she claims as "her" house.

10. In Celine and Julie’s last visit to the house, they enact a slapstick comedy routine in mime. The family members, except for Madlyn, wear ghastly grey-green make-up and repeat their roles. Celine and Julie disrupt the linearity of the previous composition, while Olivier and Sophie’s posture still echoes the strong verticals of the architecture.

The women plop a crown on Olivier’s head to make fun of his authority, put a tango on, and move together in a joyous dance toward the foreground, bursting through the constraint and gloom with their white clothes and action, moving straight toward us.

Communicating in the liberated zones

11. Celine uses the library to enact a transgressive performance in public space, Julie’s workplace, to get Julie’s attention. Celine claps books on the table and draws around her hand with a red pen, her mouth set in a childlike display of concentration.

Feeling observed, Julie simultaneously stamps her finger in the red ink pad and marks a piece of paper. The psychic doubling, the tactics of women’s flirtation, the exaggerated expansiveness of Celine’s gestures, the unnaturally heightened sound, and the playful use of public space — all these cinematic tactics and fictional developments are used to mix up the ordinary cinematic presentation of social and personal cues.

12. In the hallway outside Julie’s apartment, Celine continues her performance yet also seems genuinely hurt.

She shows up bloody and needy, an invitation to both mothering and being mothered. Her open body posture and downcast facial expression indicate vulneability.

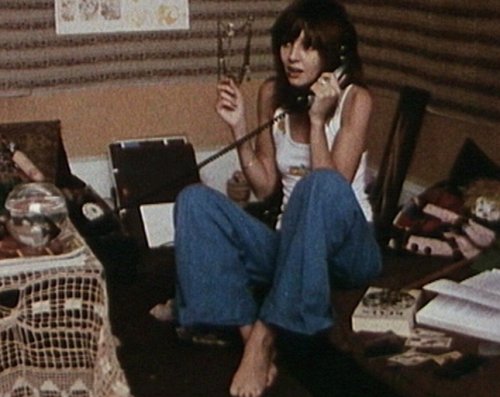

13. Both in the opening chase and here, Julie ransacks through and appropriates Celine’s things, including many toys Celine has in her purse (does a purse symbolize a female "vessel" ?). Julie’s body language is like that of both women while in the apartment : open, active, expressive and "unladylike." Inexpensive possessions lie around in disarray.

Julie tosses Celine’s things out, tries an alarm clock that goes off, copies the data from Celine’s carnet, puts some of Celine’s clothes in the closet, and hides other things by the corner of the couch. Both women seem greedy to initiate intimacy.

14. Julie’s bed is in a loft. We see no lovemaking, only Julie munching the toast she’s bringing up to Celine. Each woman will enact the ritual of bringing the other breakfast in bed ; the second time, we observe that each has her "side" in the bed.

The duplication of situations and the similar stances each woman adopts indicates that theirs is a relation between equals. The sequences connote "sexuality" but only indirectly.

15. Women usually protect themselves from being seen this way — scratching themselves, picking their toes, sprawling out on the floor, or making faces while listening to someone. Male film stars like Marlon Brando and James Dean have used such gestures as indicators of the romantic hero’s independence and social revolt. Here Celine is talking to Gilou, lowering her voice to imitate Julie. She is seen hitting her nose with a daisy, which she sticks in the fish bowl, and she rummages through everything in Julie’s place.

16. Celine and Julie each demolish the other’s previous entanglements. Here wearing white and meeting Gilou in a park as Julie, Celine destroys Gilou’s romantic pretensions. The sequence also parodies traditional film romance, with its centered composition, sharp differentiation between foreground and background, and dancing as in a musical comedy. Gilou utters passionate, poetic remembrances about his and Julie’s childhood romance, and Celine strikes a pose like a model with each phrase. His posturing, romantic fantasy, and passion are reduced to nothing as Celine pulls down his pants, he pulls off his tie, and then she declares, "Go jack off. »

17. Julie had hung up three dolls, two female and one male, below a rude diagram she drew of the mystery house, the male doll being upside down. Here, using "Solomon’s judgment" to decide which woman killed Madlyn, Celine and Julie tear the male doll in half, only to discover that "he dosn’t have any." Celine and Julie’s clothes, gestures, and agility are "tomboyish. Symmetrically posed, they act as a team.

Female potency is usually represented as "unnatural" and transgressive, and here Celine and Julie’s play consists of rending the male into shreds, which makes the sequence a joke about the image of the "castrating bitch. »

18. After one is ejected from the house, Celine or Julie pick the other up and go to a cab magically waiting for them. Julie first wrapped the LSD candy in a Kleenex ; later she brought a special little box to store it in. Here Julie in the mothering role holds and touches Celine. Notice the gestures and the style of nurturance.

From Celine’s dependency while sitting bruised on the stairway to the mutual support seen here, the women grow together, and by the end of the film reach the point where they take active control over their lives.

19. The women’s similar garb, mutual contact, bodies relaxed against each other, and similar arm positions indicate the kind of physical symmetry associated with intimacy. That evening they had read Gilou’s protest letter to Julie out loud together, hugging each other, prancing, making fun of him and acting physically and emotionally as if they were one.

Here, having tripped with the magic potion they concocted in the bowl on the table (they gave some to the fish), they are laughing about their adventure and are also afraid.

20. The two women "put on" Olivier as he looks in the mirror. He doesn’t see them and they act as if they are each other’s mirror image.

Women are usually the "background," the arrangers of the milieu in which the real, male-oriented action is supposed to occur. In fact, as marginal people, Celine and Julie know what’s going on and that it’s not for them. They move from being in the background and complicitous in the crime to demolishing it.